Chapter 2The impact of everything

The what, how and why of the Upright net impact model

The Upright net impact model is a mathematical model of the economy that produces continuously updated estimates of the net impact of companies. It utilizes an information integration algorithm that consolidates data from humanity’s accumulated scientific knowledge and public statistical databases.

Upright’s net impact model is the company’s main tool in pursuing its mission: to incentivize companies to optimize their net impact. To serve its purpose, the model is designed to satisfy the following requirements:

- Measure net: The model must consider both costs and gains, and provide their net sum. This is a minimum requirement for informing decision-making on resource allocation.

- Comparability: All estimated costs and benefits produced by the model must be comparable. Comparisons must be possible within industries, across industries, and across different types of costs and benefits.

- Comprehensiveness: The model must consider all types of costs and gains, not only e.g. environmental costs or financial gains. This is a minimum requirement for understanding the whole value creation of a company and thus informing decision- making on resource allocation.

- Whole value chain: The model must capture the cost and benefits created in the entire value chain of a company, not just what happens inside the company or how it affects its immediate stakeholders (shareholders, clients, employees).

- Adaptable values: The model must not assume universal values, and must instead accommodate for the fact that every individual decision-maker has a different view of value and different optimization criteria when making decisions in different roles. The model must also be practical and provide reasonable fact-based defaults for these sets of values.

- Scalability: The marginal cost of estimating the impact of an additional company should be close to zero, meaning that it should not require any manual work. This is required for large-scale adoption and thus significance of the data.

The primary data source for scientific literature for the Upright net impact model is the CORE database, which contains approximately 210 million scientific papers. That represents approximately 50% of all scientific articles that have ever been published.

Public statistical databases used by the Upright model include The World Bank database, OECD Structural and Demographic Business Statistics (SDBS), OECD Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), The Global Burden of Disease database from IHME, The Global Peace Index, and others.

Does the Upright Project model mark the beginning of an era where net positive impact and investment returns are in full alignment?

[Upright's] greatest innovation lies in the modelling of the value chains of all the goods that are traded globally and in teaching a neural network to understand and establish these relationships.

An in-depth introduction to the model is available in the white paper Estimating the net impact of companies, available online at uprightproject.com/whitepapers/model.

From “good vs. bad” companies to understanding optimization criteria

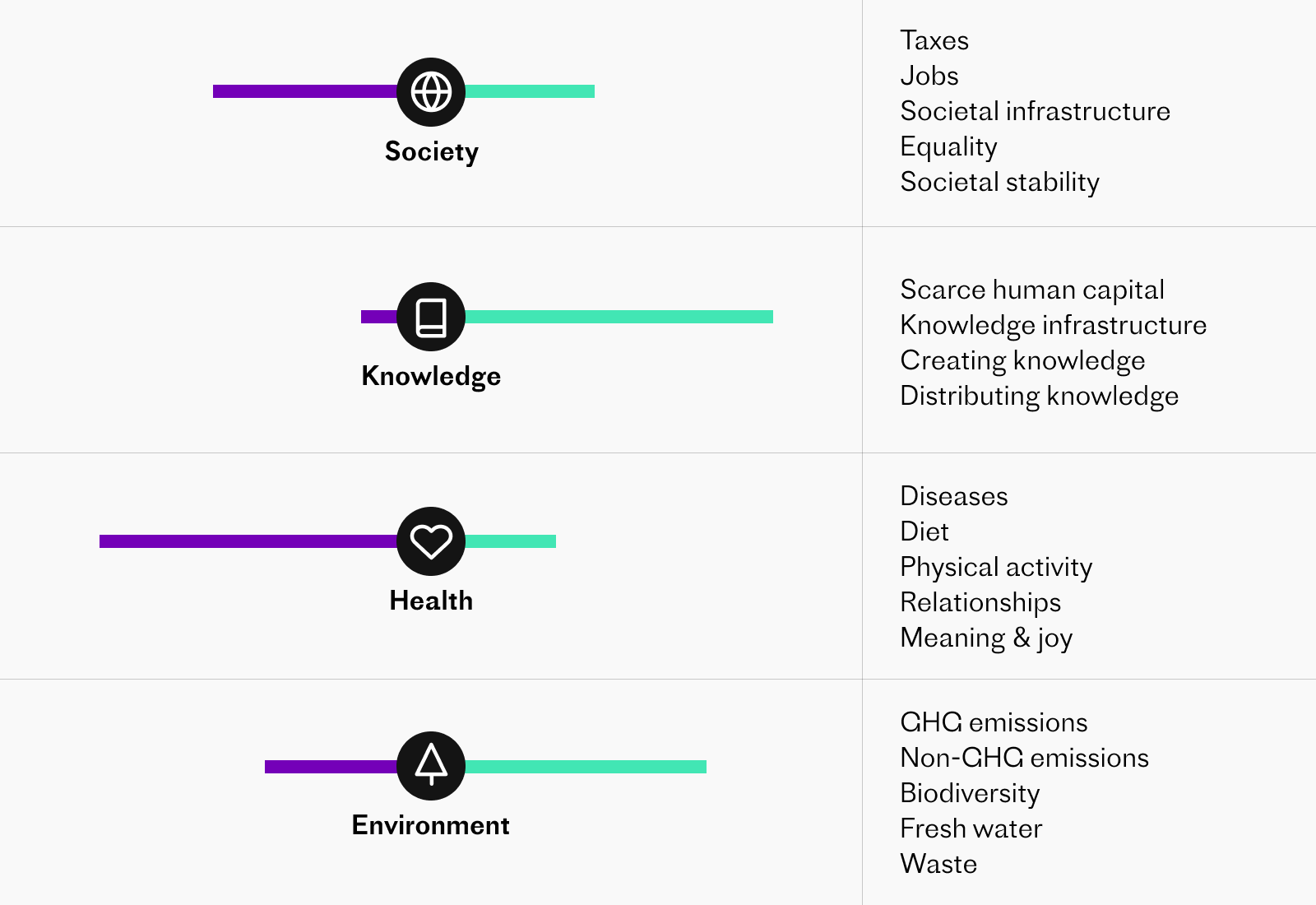

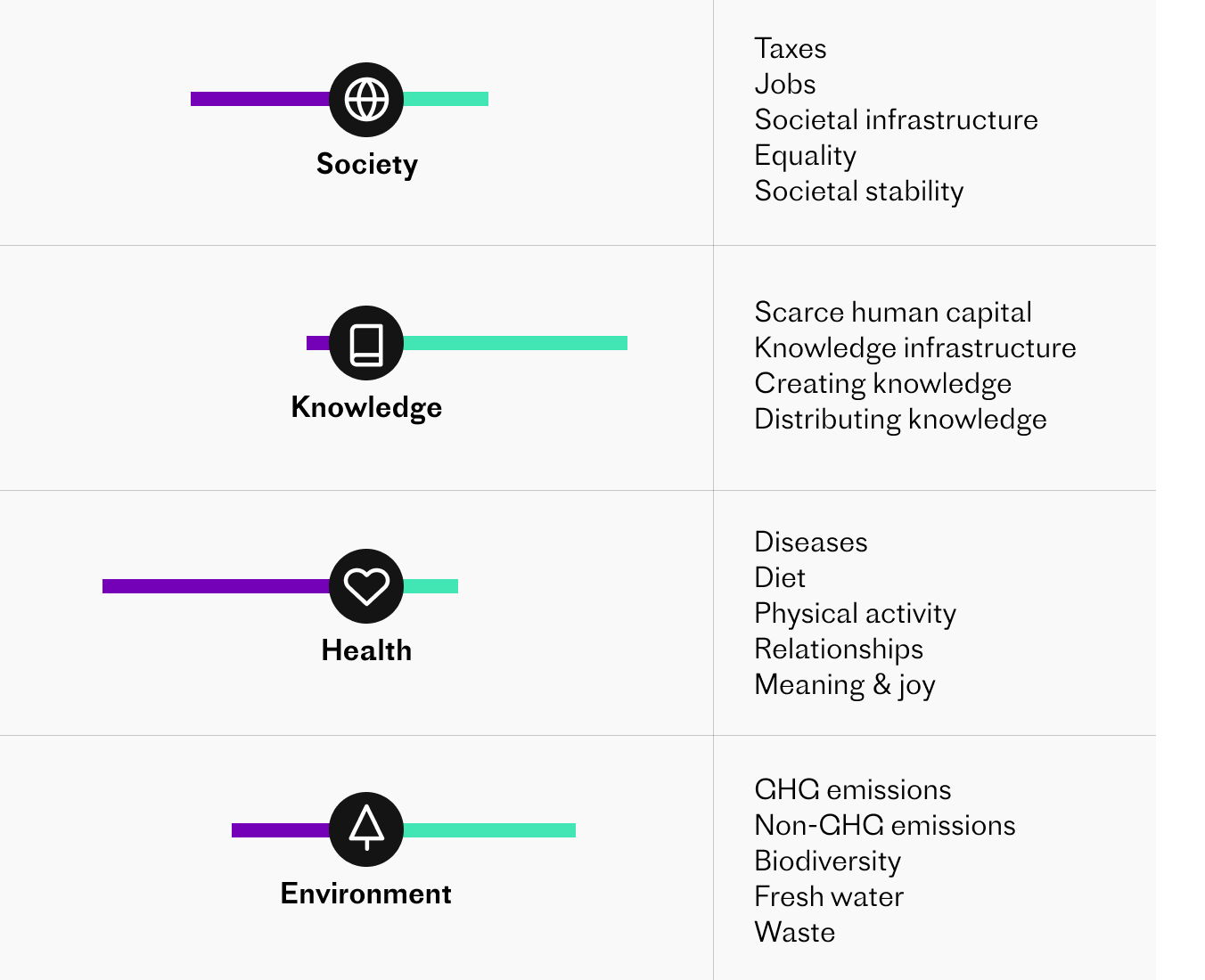

What are the top 10 companies in Sweden impact-wise? As tempting as that question could be to ask, it’s not really an intellectually sound one. Depending on what is optimized, the answer varies quite a bit. Taxes? Jobs? Fighting climate change? Health of people, creation of knowledge, equality? All of the above with different weights on each?

Up until today, we have been used to impact metrics that somehow answer the question: how good is this company for the surrounding world? The desire for an answer like this is obvious: it would make the lives of investors, consumers, job seekers and governments a lot easier if we could simply know which companies are absolutely better than others.

Unfortunately, that question is too vaguely posed. Depending on what you want to optimize, the list of the “best companies” varies. For example, if we only want to understand which companies pay the most taxes, tobacco companies are pretty strong candidates. However, if we ask which companies are the most beneficial for people’s health, the answer would obviously be different.

What is the take-away? Simple one-dimensional ways of understanding impact, or dividing companies into nice and naughty ones, are naive and outdated.

Simple one-dimensional ways of understanding impact, or dividing companies into nice and naughty ones, are naive and outdated.

Outsourcing values to rating makers

That’s why we made the choice early on when designing the basic architecture for the Upright net impact model to cater for varying optimization criteria. And whenever working with an asset manager, city or company, we strongly recommend them to translate their own investment strategies and priorities into a value set.

Why? Because one of the key points we want to make is that Outsourcing the choice of values to rating makers does not make the choices go away.

The paradox of “no subjective choices”

“But we can’t compare health and the environment. Let alone jobs and taxes!” This is a common first response to estimating the net value creation of companies. The counter argument is simple: But we do compare them. Every day. We make choices between different value categories. We have limited time, money or attention, and we decide to allocate them over a myriad of value dimensions: our family, our health, the health of others, the economy, the environment, and so on.

The same happens in leading businesses and making investments decisions. A pension fund that has decided to invest X Euros in aircraft manufacturing and Y Euros in new medical technology has made a number of choices.

We are just not conscious of the choices we make as the trade-offs often make us uncomfortable and the analytical thinking required is difficult. However, as adults, we need to deal with trade-offs and face the fact that we cannot optimize everything at the same time.

As adults, we need to deal with trade-offs and face the fact that we cannot optimize everything at the same time.

Users determine the optimization criteria

How does this show concretely in this report? At the end of each Dataset, you can see which companies come out as the 10 “winners” through the lenses of different stakeholders: asset owners, asset managers, most sought-after workforce evaluating jobs, millennials, and individuals or investors who prioritize health or creation of new knowledge over other impact dimensions.

You can also visit The Upright Net Impact Platform to stress-test companies and funds against values of different stakeholders in real time. Whichever way you do, we hope you remember one thing. Whenever you hear about a new list that rates sustainability, impact or responsibility, remember to ask:

What is assumed of the relative importance of different value dimensions? Are all the value categories equally significant for your decision-making, or would you need to emphasize some more than others? Are you able to stress-test the same list under different sets of values and goals?

Because the assumptions exist, whether they are made visible or hidden behind frameworks.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals are the most widely adopted framework for impact. Why are they not used in this report?

When we started to build the Upright net impact model in 2017, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals were among the key frameworks we studied rigorously. The aim was to use or form a framework that is approachable to business leaders, scientists and everyman alike, avoids jargon or artificially complicated terms, and covers all areas in which companies can either create value or use resources.

We were hopeful about the SDGs: a great framework widely known and adopted by companies. However, after some careful analysis we came to the conclusion that they can not, and should not, be used for measuring net impact.

Figure 2.2.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Original image from here.

What are the SDGs good for?

The SDGs are great for creating a common understanding of what we as humanity should focus on: the biggest sustainability challenges of our time. However, they are not an intellectually sound and solid way for measuring net impact.

The SDGs can not, and should not, be used for measuring net impact.

Why?

Firstly, the SDGs do not cover all categories in which companies can create value or use resources. The missing value categories include for example creating tax income that finance our schools and hospitals, creating or using scarcely available human capital, creating jobs, and creating and distributing knowledge.

This is problematic in measuring net value creation because not all areas of impact will be considered.

Secondly, some categories are included multiple times. For example, decreasing greenhouse gas emissions would show up in at least SDGs 3 (Good Health and Well-being), 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and 13 (Climate Action). This is troublesome in measuring as it leads to double-counting.

The SDGs do not consider the resources used to pursue one goal.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the SDGs do not consider the resources used to pursue one goal. This is problematic as resources are limited and thus the net impact of actions needs to be considered. A company might pursue one SDG while harming another. Unless the net sum of these costs and gains is considered, the benefit for one SDG does not yet indicate net positive impact for said company.

The danger of using the SDGs as themes

Additionally, the SDGs are largely mis-used as themes a company’s business can be linked to. For example, startup report State of European Tech links startups to the SDGs in its chapter on Purpose, implying that such links would then mean the said startups were “purpose-driven”. As one concrete example, they link “meat substitute” startups to solving the Zero Hunger challenge, i.e. SDG 2 - which makes pretty much no sense at all.

This thematic linking has taken off as a common practice in larger corporations, too: having a good old brainstorming session or buying a consulting project to determine which SDGs have the closest link to what a company is doing, and then printing them in the annual report as “evidence” that the company is somehow good for the world. It is actually quite hard to think of a company whose activities could not be loosely linked to at least one of the SDGs. However, this says nothing about the impact: it can be net positive, net neutral or net negative.

One interesting example is delivered by oil company Shell, which suggests in its own report that it contributes positively not to one or two, but all of the 17 SDGs.

Any company can be thematically linked to at least one of the SDGs. It does not mean the company’s operations are net positive.

We currently use the SDGs, are we doomed?

No! The next step is to start measuring how efficiently you pursue your impact goals, whether they are listed as one of the SDGs or not. Which resources you use, what you get done. Your net impact. Bonus? Communicating this is honest, fresh and to-the-point, and respects your audience - your employees, investors, clients, and the talent you want to attract.